Today, we have the first instalment of a series of article-commentaries upon HellWard by editor David Russell of Waterloo Press. Offering startling insight into the poem, this commentary will give readers not merely a summary of the narrative thread of HellWard but also tools to dissect its deeper themes and meanings. For those new to reading poetry, it provides a methodology for breaking down poetic language and symbolic meaning – effectively demonstrating how to read with a critical eye. But for more experienced readers it also offers an alternative prism through which to view the theological poeticism of “England’s epic poet”, James Sale.

In part 1, David Russell examines the introduction to HellWard and its first canto.

Sale opens his preface with a clear approach to epic poetry. He rejects the dogmatic and the doctrinaire. Epic has an essence beyond any conscious motivations of its writer/s: “a profound belief system behind the overt belief system.” The Leitmotifs of this work are the concepts of free will, and the near-death experience. He sees free will and the concept of Hell as being related, and as unpopular amongst the doctrinaire.

“Epics are all about journeys to Hell and back.”

The author takes Dante as his guide, both as inspiration for his composition, and as a guide/mentor in the narrative.

“Dante elevated human decision-making to a point where even God cannot reverse the consequences of such decisions.”

The author had his own near-death experience with a Malignant Sarcoma in 2011. This decisively related stark reality to his Dantesque vision:

“The ward system could represent, loosely, the Circles of Hell that Dante describes.”

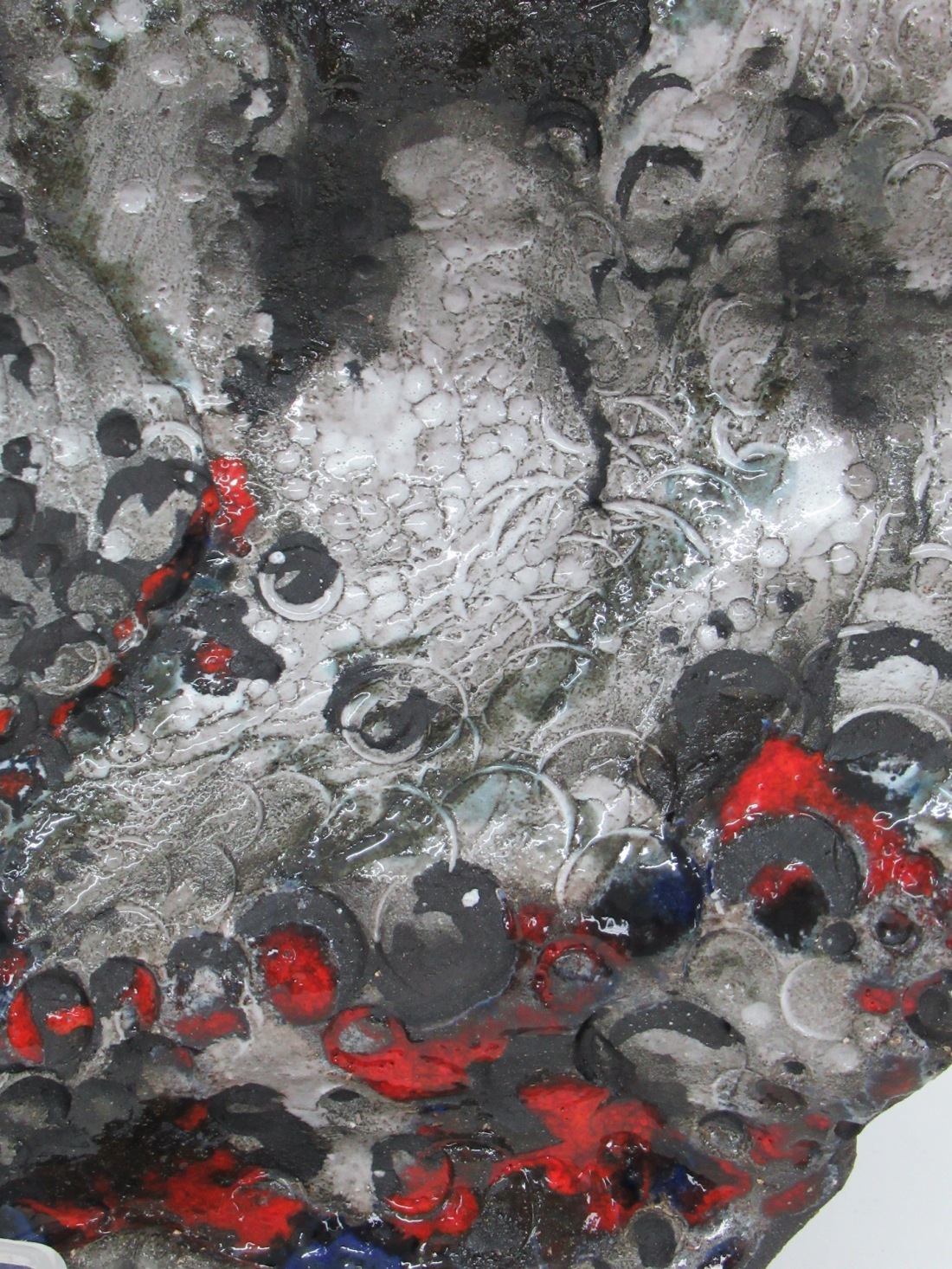

In Canto 1, James is hospitalised. Through the sheer agony of near-death, he gains enlightenment and vision:

“In total despair and pain, the poet is invaded by this force at the point where the surgeon’s knife went in and cut him; and so, unexpectedly, enters a state of paradise, albeit briefly; and from this moment he is enabled, and sent to enter all the Wards of hell to find the meaning of loss.”

Through this enlightenment, he recognises that the Path to Hell is paved with good intentions:

“The misery, unintended, unplanned

That characterised the fools who sought to build

A better world.”

He sees the folly of overrating the influence and power of politics and science. A true vision of the world parallels the full exposure and dissection of the body under surgery. So with the doctrinaire:

“Yet for all that building, they built one tomb

Called planet Earth – polluted, warmed and dying,

Neglecting the while to study, exhume

The corpse of what the century was frying.”

He realises that he must ‘make his descent’ work against that neglect. To that end, “I saw myself for poetry is scrying”. In his extremity, he calls on Calliope, the Epic Muse, to make sense of the modern world. He realises his mission:

“. . . each human hides that face

Divine, which is our task, within our will,

To reveal at last . . .”

There is a ‘face divine’ in every human, however, sick, aged, degraded or perverted. In his appeal to Calliope, he recognises that grand Paradox: “That Love that Dante saw created hell.” This is the balancing contrast of the sublime constellations.

James is on his Quest for the Grail, to ascend to Dante’s 9th Heaven. A powerful sense of destiny, tinged with despair:

“You know the golden god and how he breaks

The proud. I came myself near history,

Despite a false summer then broken out,

Collapsing quite incomprehensibly.”

Epiphany prevails over chaos. He relates his quest to his surgery. There was some sense of hope and optimism through the surgical revelation of the diseased tissue. The cancer is a death-threat:

“Refusing life, wanting in death to mesh

With me, an apt image of evil’s mind,

Small gains to build one vaulting emptiness,

At last undo what so much love designed.”

Perhaps not so perversely, part of him longed for the release of death, for his spirit to ascend: “Out of my body, sight soared to space.” He gets a vision of his eternal, post-mortem self: “There, close-up, I saw not chaos, / But its just opposite . . . a star formed in deep space.” But this astral body is subject to a greater power “– One flick, it revelled forward on its round.” What agency/power administers the flick? God? The same question applies to “the whole cosmos rent Into parts” and “each atom purposeful, sent”.

James is acutely conscious of his plight: “Powerless to do evil, much less good” He makes an appeal to God, who is life itself, who is the plan. He fears he might have to stay forever, ‘in his dark rut’. Then comes the Divine Revelation through surgery:

“There, at the point the surgeon made his cut,

At that point exactly I felt God’s blow

In me – so in me that nothing could stop

Its force, its flow and in one instant all changed,

As if mortality itself were shut

Off, and for it something brand new exchanged:

I mean that pain, in body and mind, ceased,

As suffering, past and present, was expunged . . .”

He attains a state of peace and freedom, but this is also deeply disturbing:

“And I aware of some awful purity:

A whiteness of light, which recalling ever

I quake within, tremble before to Be . . .”

In spite of this, he weeps tears of joy, being in the benign embrace of God. Peace and wellbeing prevailed over malignant chaos, evoked by a searing image of mass deaths of bees. God prevails benignly over time and matter:

“Time slowed to tripartite significance,

Future ahead, and present, a new past

In which what was random had His Presence,

Vital, pervading all moments, all mass,

Nothing beyond reaching beyond His reach,

That reach, and His hand, the net He had cast.”

His power is all-pervasive, but he is “not some distant God”. He opens the door for the Poet to proceed with his journey. The depth of horror points the way to enlightenment:

“If seeing my own horror and its toll

Might let light intrude, penetrate my soul.”

To check out David Russell’s Poetry Express newsletter, please click here.